As Diabetes Education Specialists and advocates, we see first-hand how healthcare inequalities impact the health of under-resourced communities.

Just as diabetes is systemic, affecting the entire body, so are the disparities in our public and private healthcare systems.

This is not only a result of public policies, healthcare education, medical racism, and medical classism, but also access to nutritious whole foods, stable housing, insurance coverage, and even enough time in the day to focus on one’s health.

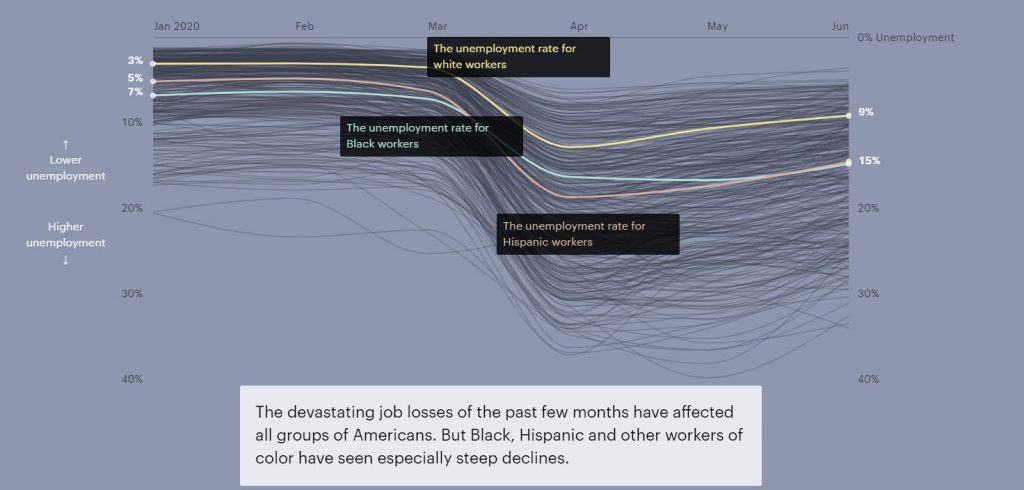

Under the COVID-19 pandemic, these disparities have become even more apparent.

“Black and Latino patients are two to three times as likely as white patients to be diagnosed with COVID-19, and more than four times as likely to be hospitalized for it. Black patients are more than twice as likely to die from the virus. They also die from it at younger ages“ wrote Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Oncologist, bioethicist, and vice provost of the University of Pennsylvania and Risa Lavizzo-Mourey, Professor at the University of Pennsylvania for The Atlantic.

Acknowledging these perforations of care is an important first step towards a more inclusive healthcare system. This reparative practice can result in more positive outcomes and improve the quality of life for many.

Insurance Coverage & Reimbursement Rates

Equal access to healthcare coverage is key.

The economic impacts of the pandemic have widened the gap in insurance coverage. Around 12 million people living in the U.S. lost employer insurance due to the pandemic, with higher unemployment rates for Black and Latino workers (see above graph).

Since the implementation of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) the number of uninsured individuals and families was reduced. However, 15 states opted out of the widening of programs like Medi-Caid under ACA.

For those insured under Medi-Caid, there is still the hurdle of finding a provider that accepts their insurance. This is because many healthcare professionals do not accept Medi-Caid due to low reimbursement rates.

Initially, the ACA increased rates for providers who accepted Medicare and Medi-caid. But they have decreased over time and with that decrease, the number of doctors accepting or even scheduling individuals with Medi-Caid decreased, as well.

“A 2014–15 survey showed that only 68 percent of family-practice physicians accepted new Medicaid patients, while 91 percent accepted those with private insurance,” Ezekiel J. Emanuel and Risa Lavizzo-Mourey.

In addition to raising overall fees for service, implementing a system in which healthcare providers are reimbursed based on health outcomes can be a way to hold us accountable to provide a high level of care, despite factors such as race, gender, sexuality, or class.

Unlearning Medical Biases & Increasing Representation

Medical discrimination is pervasive.

A study conducted earlier in the pandemic found “that doctors were less likely to refer symptomatic Black patients for testing than they were to refer white ones.”

It has also been studied that white medical students and residents rate pain lower for Black people who are experiencing similar symptoms to white people. This bias impacts their care recommendations and the study found lower accuracy of treatment plans for the Black person’s case example.

Educating ourselves on the history of medical racism and classism while engaging in implicit bias training can help us unlearn these inaccurate assumptions.

Representation matters for Healthcare Providers.

Lack of representation often stems from a multitude of factors, such as discriminatory admissions or hiring practices.

An experiment conducted in Oakland found that involving Black doctors in treatment plans reduced the cardiovascular mortality gap by 19% for Black and white men.

Another example of why representation matters are reflected in how commonly medical texts only show white skin tones. Because of this, Malone Mukwende, a 20-year-old medical student is working on a book to show what symptoms look like on darker skin.

Systemic changes begin with each of us.

Educating ourselves on discriminatory medical practices both for healthcare professionals and the people living with diabetes with whom we work with is a great first step to moving towards a more inclusive medical system.

Written by Bryanna, our Director of Operations & Customer Happiness

Read more from The Atlantic article by clicking here. For more information on racial disparities in the treatment of pain click here. For Malone Mukwende’s story click here.

Sign up for Diabetes Blog Bytes – we post one daily Blog Byte from Monday to Friday. And of course, Tuesday is our Question of the Week. It’s Informative and FREE! Sign up below!

[yikes-mailchimp form=”1″]

Accreditation: Diabetes Education Services is an approved provider by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider 12640, and Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR), Provider DI002. Since these programs are approved by the CDR it satisfies the CE requirements for the CDCES regardless of your profession.*

The use of DES products does not guarantee the successful passage of the CDCES exam. CBDCE does not endorse any preparatory or review materials for the CDCES exam, except for those published by CBDCE.